by Sheila Doucet, AAWE Paris

One’s senses are constantly solicited at COP. The 2024 UN Conference of the Parties on Climate Change (COP29) in Baku, Azerbaijan was no exception: handmade or industrial messages either screaming for immediate action or calmly stating a platitude for an inspirational vision of a future worth striving toward, carpeted passages muting footsteps as hundreds tread toward meetings, discussions, panels, plenaries and/or protests – depending on one’s profession, inclination or mood. The intoxication of information intake. The intensity of participation. And a solitary piece of art representing the intersection of climate action and human rights.

In the midst of all the brouhaha, I first noticed an intriguing bronze sculpture as it sat on a civil society stand. I was on my way to a meeting, but confidently thought I would find it later. You can imagine my disappointment when I returned the next day to an empty spot – and total surprise two days later when I stumbled upon the same statue in a completely different location, this time with its creator literally in tow.

In the midst of all the brouhaha, I first noticed an intriguing bronze sculpture as it sat on a civil society stand. I was on my way to a meeting, but confidently thought I would find it later. You can imagine my disappointment when I returned the next day to an empty spot – and total surprise two days later when I stumbled upon the same statue in a completely different location, this time with its creator literally in tow.

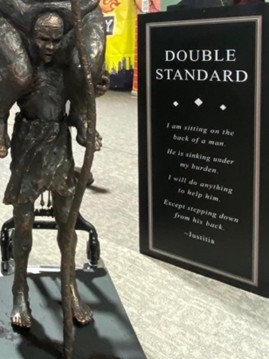

The artist is Jens Galschiøt, a renowned Danish sculptor whose works are intended to “create international happenings to highlight the current imbalance in the world.” The sculpture that caught my attention is entitled Double Standard. It depicts an obscenely obese woman delicately balanced on the shoulders of a thin, frail man. Since its origin in 2002, this sculpture has become known worldwide as a symbol of inequality and climate justice, wherein the woman embodies the excessive consumption patterns of the Global North weighing down the impoverished man, who personifies the toil of Global South countries.

Double Standard reminds us that over the past two centuries, policies and industrial practices adopted by Global North countries caused our current environmental crisis, and that the effects of climate change – rising sea levels, extreme weather, biodiversity loss, etc. – threaten basic human rights such as the rights to life, health, food, water and shelter. Climate justice addresses the unequal impact of climate change on vulnerable populations, linking environmental sustainability with fairness and equity. Governments therefore have a duty to mitigate climate change and ensure that adaptation measures respect and promote human rights. The imbalance is that Global South countries have collectively and historically contributed the least to current levels of greenhouse gas emissions, yet are not spared the negative effects of climate change. The injustice is that economically developed, industrialized countries steadfastly refuse to provide adequate funding in a timely fashion for low- and middle-income countries to modernize, adapt and protect themselves from the damage caused by the very crisis the richer, heavily industrialized countries created.

The pamphlet accompanying Double Standard introduces the woman as “Justitia, The Western goddess of Justice.” Justitia carries a small scale in her right hand. However, the sculptor declares that she embodies “self-righteousness rather than justice.” She does not wear a blindfold – and is decidedly not blind. She proclaims: “I am sitting on the back of a man. He is sinking under my burden. I will do anything to help him. Except stepping down from his back.” She is therefore well aware of her role, but unwilling to change her behavior to alleviate his suffering. Therein lies the double standard. A just solution must place equity and human rights at the core of decision-making and action on climate change.

The pamphlet accompanying Double Standard introduces the woman as “Justitia, The Western goddess of Justice.” Justitia carries a small scale in her right hand. However, the sculptor declares that she embodies “self-righteousness rather than justice.” She does not wear a blindfold – and is decidedly not blind. She proclaims: “I am sitting on the back of a man. He is sinking under my burden. I will do anything to help him. Except stepping down from his back.” She is therefore well aware of her role, but unwilling to change her behavior to alleviate his suffering. Therein lies the double standard. A just solution must place equity and human rights at the core of decision-making and action on climate change.

At COP21, held in Paris in 2015, governments agreed upon a collective, tangible goal based on validated science: hold the increase in the earth’s climate to 1.5 degrees Celsius to preserve various earth system processes in balance. In the succeeding eight COPs, negotiations have centered on increasingly precise mechanisms and national commitment schemes to meet this goal. This has been an intricate and excruciatingly slow process – especially from the perspective of the thin man handicapped by carrying a hefty burden which is unwilling to change. By taking Double Standard to COP29 in Baku, Galschiøt also echoes the interconnection between human rights and the environment as stated in this declaration from the UN Development Program (UNDP):

“All people should have the agency to live life with dignity. However, the climate crisis is causing loss of lives, livelihoods, language, and culture, putting many at risk of food and water shortages, and triggering displacement and conflict."1

Climate justice therefore calls for a more inclusive and sustainable approach to addressing the global climate crisis.

A climate justice framework invites us to sit with these issues. It invites us to cloak our inquiry of world and/or local events to include both the roots of and the consequent impact of government, corporate and personal decisions through a wider range of perspectives.

A climate justice framework invites us to sit with these issues. It invites us to cloak our inquiry of world and/or local events to include both the roots of and the consequent impact of government, corporate and personal decisions through a wider range of perspectives.

Art is an open door to integrate multifaceted, intricate levels of Story. Through the prism of a piece such as Galschiøt’s Double Standard, we are invited to (re)consider relationships. Tell me – did you assume yourself to be the woman sitting comfortably on the back of the other – or are you actually the man? The sculptor invites us to ponder Justitia’s motivations, the source of her belief systems and her decision to continue “business as usual” in spite of acknowledging her position and its consequences. It entreats us to absorb deeper truths about the inner workings of the world within which we live, the world in which we are inadvertent yet active players. We have all heard economic, political and scientific data points that aim to explain the current climate crisis. We therefore know the harms fossil fuel emissions wreak on the environment, how the dangerous levels of accumulation destabilize the inner workings of our delicately balanced planetary mechanisms, how these effects harm the intertwined dances of survival for fauna and flora alike. Art is a viable tool in an environmentalist’s arsenal. It viscerally captures the truth of a moment, be it from an entirely new, slightly different or deeply held perspective. Art touches hearts – and touching the heart is where human compassion and understanding live.

References:

1 Climate change is a matter of justice – here’s why | UNDP

Sources:

Website of the artist, Jens Galschiøt and his presence at COP29:

Climate Justice Global Alliance | UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs

Seeking additional information on the topic of climate justice? Dean’s Lecture Series: A Conversation with Distinguished Professor David Pellow is a comprehensive recorded lecture on environmental justice from the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability. David Pellow is the Delhsen Chair & Professor of Environmental Studies and Director of the Global Environmental Justice Project at the Univ. of CA, Santa Barbara (Dec. 6, 2023)

All photos by the author.