Malaria: General Description

Malaria is a life-threatening parasitic disease transmitted by mosquitoes. It was once thought that the disease came from fetid marshes, hence the name mal aria, ((bad air). In 1880, scientists discovered the real cause of malaria, a one-cell parasite called plasmodium. Later they discovered that the parasite is transmitted from person to person through the bite of a female Anopheles mosquito, which requires blood to nurture her eggs. Occasionally, transmission occurs by blood transfusion or congenitally from mother to fetus. Although malaria can be a fatal disease, illness and death from malaria are largely preventable.

Malaria in humans is caused by one of four protozoan species of the genus Plasmodium: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, or P. malariae. P. vivax and P. falciparum are the most common and falciparum the most deadly type of malaria infection. Plasmodium falciparum malaria is most common in Africa, south of the Sahara, accounting in large part for the extremely high mortality in this region. There are also worrying indications of the spread of P. falciparum malaria into new regions of the world and its reappearance in areas where it had been eliminated.

The malaria parasite enters the human host when an infected Anopheles mosquito takes a blood meal. Inside the human host, the parasite undergoes a series of changes as part of its complex life-cycle. Its various stages allow plasmodia to evade the immune system, infect the liver and red blood cells, and finally develop into a form that is able to infect a mosquito again when it bites an infected person. Inside the mosquito, the parasite matures until it reaches the sexual stage where it can again infect a human host when the mosquito takes her next blood meal, 10 to 14 or more days later.

Occurrence

Today approximately 40% of the world's population, mostly those living in the world's poorest countries, is at risk of malaria. The disease was once more widespread but it was successfully eliminated from many countries with temperate climates during the mid 20th century. Today malaria is found throughout the tropical and sub-tropical regions of the world and causes 300 - 500 million acute illnesses and at least one million deaths annually.

Ninety per cent of deaths due to malaria occur in Africa south of the Sahara, mostly among young children. Malaria kills an African child every 30 seconds and may account for as much as 25% of child mortality. Many children who survive an episode of severe malaria may suffer from learning impairments or brain damage. Pregnant women and their unborn children are also particularly vulnerable to malaria, which is a major cause of perinatal mortality, low birth weight and maternal anemia. Malaria, together with HIV/AIDS and TB, is one of the major public health challenges undermining development in the poorest countries in the world.

Clinical Presentation

Malaria symptoms typically appear about 9 to 14 days after the infectious mosquito bite, although this varies with different plasmodium species and may be delayed up to several months after the initial exposure. Typically, malaria produces fever, headache, vomiting and other flu-like symptoms; these symptoms can occur at intervals.

If drugs are not available for treatment or the parasites are resistant to them, the infection can progress rapidly to become life-threatening. Malaria can infect and destroy red blood cells, causing anemia and jaundice, and it can clog the capillaries that carry blood to the brain or other vital organs, causing seizures, renal failure and death.

Control and Prevention

Malaria parasites are developing unacceptable levels of resistance to one drug after another and many insecticides are no longer useful against mosquitoes transmitting the disease. Years of vaccine research have produced few hopeful candidates and although scientists are redoubling the search, an effective vaccine is at best years away.

Science still has no magic bullet for malaria, and many doubt that such a single solution will ever exist. Nevertheless, effective low-cost strategies are available for its treatment, prevention and control and the Roll Back Malaria global partnership is vigorously promoting them in Africa and other malaria-endemic regions of the world. Mosquito nets treated with insecticide reduce malaria transmission and child deaths. Prevention of malaria in pregnant women, through measures such as Intermittent Preventive Treatment and the use of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs), results in improvement in maternal health, infant health and survival. Prompt access to treatment with effective up-to-date medicines, such as artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), saves lives. If countries can apply these and other measures on a wide scale and monitor them, then the burden of malaria will be significantly reduced.

By Karen Lewis, M.D.

Adapted from WHO and CDC sources:

- http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs094/en/index.html

- http://www.cdc.gov/travel/diseases/malaria/index.htm

{mospagebreak}

Malaria: Prevention with Insecticide-Treated Mosquito Nets (ITN's)

Most malaria-carrying mosquitoes bite at night. Mosquito nets, if properly used and maintained, can provide a physical barrier to hungry mosquitoes. If treated with insecticide, the effectiveness of nets is greatly improved, generating a chemical halo that extends beyond the mosquito net itself. This tends to repel or deter mosquitoes from biting or shorten the mosquito s life span so that she cannot transmit malaria infection.

Trials of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) in the 1980s and 1990s showed that ITNs reduced deaths in young children by an average of 20%. Unfortunately, ITNs can be expensive for families at risk of malaria, who are among the poorest in the world, and cost is not the only barrier to their effective use. Often people who are unfamiliar with ITNs, or who are not in the habit of using them, need to be convinced of their usefulness and persuaded to re-treat the nets with insecticide on a regular basis.

In some areas where mosquito nets are already widely used, it has been estimated that less than 5% are re-treated to achieve their expected impact. WHO has worked with mosquito net and insecticide manufacturers to make re-treatment as simple as possible. However, the best hope lies with newly developed, long-lasting treated nets which may retain their insecticidal properties for four to five years the life span of the net thus making retreatment unnecessary.

One of the targets set at the Abuja Summit in April 2000 was to have 60% of populations at risk sleeping under ITNs by 2005. This will require 32 million mosquito nets and a similar number of insecticide re-treatments each year. To achieve this, much work still needs to be done to make ITNs affordable, widely available, and most importantly, appealing to the consumer. A variety of different approaches are being taken to promote ITN use, reduce their cost and ensure their quality:

- Social marketing schemes, health education campaigns and the development of a 'net culture' through promotion and publicity will all play their part in creating the necessary demand.

- In the Abuja Declaration, African governments committed themselves to reduce or eliminate the tariffs and taxes imposed on mosquito nets, netting materials and insecticides, in order to help lower retail prices. Almost 20 countries have reduced or waived such taxes and tariffs since the summit.

- Countries are also working to encourage the development of local industries and competition among them by ensuring private sector investment in manufacturing and importing mosquito nets.

- Further government action in the form of targeted subsidies, or subsidy schemes, is needed to bring ITN prices down to a level affordable to the poorest families.

- Since many mosquito nets currently in use have been distributed by NGOs or other organizations, WHO has recently drawn up a set of standard specifications for netting materials to make the procurement and quality control of ITNs easier.

- The Strategic Framework for Coordinated National Action for Scaling-up Insecticide-treated Netting Programmes in Africa (WHO/CDS/RBM/2002.42) reviews some of the generic issues frequently encountered in Africa south of the Sahara, during the integration of public and private sector activities, including issues of financing and distribution, and how limited public sector resources can be best used to provide the maximum possible long-term health benefits.

Promoting the use of ITNs

The Roll Back Malaria global partnership promotes the use of ITNs for everyone at risk of malaria, especially children and pregnant women.

To promote the use of ITNs, RBM is working to:

- organize public education campaigns in malaria-endemic areas;

- lobby for reduction or waiver of taxes and tariffs on mosquito nets, netting materials and insecticides;

- stimulate local ITN industries and social marketing schemes so that nets are available at a price everyone can afford; and

- capitalize on the potential of newly developed long-lasting treated mosquito nets.

Above: A major problem with ITNs is ensuring that they are regularly re-treated. Communal dipping sessions are a popular solution. Right: RBM is encouraging the development of local netting industries through social marketing schemes.

Treated bednets are a proven way to combat malaria, but they are still not widely used

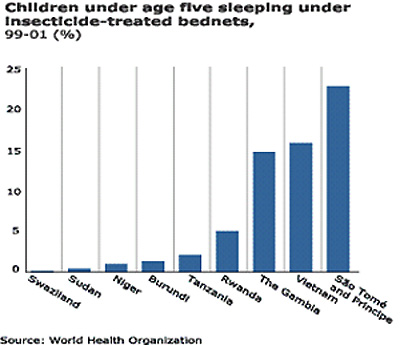

An effective means of preventing new infections is the use of insecticide-treated bed nets. Vietnam, where more than 16 percent of children sleep under treated bed nets, has made significant strides in controlling malaria. But in Africa, only 7 of 27 countries with survey data reported rates of bed net use greater than 5 percent.

By Karen Lewis, M.D.

Adapted from WHO and CDC sources: